Mosaics and Modernity: Yevgen Nikiforov’s Guide to Public Art of Soviet Ukraine

August 12, 2020

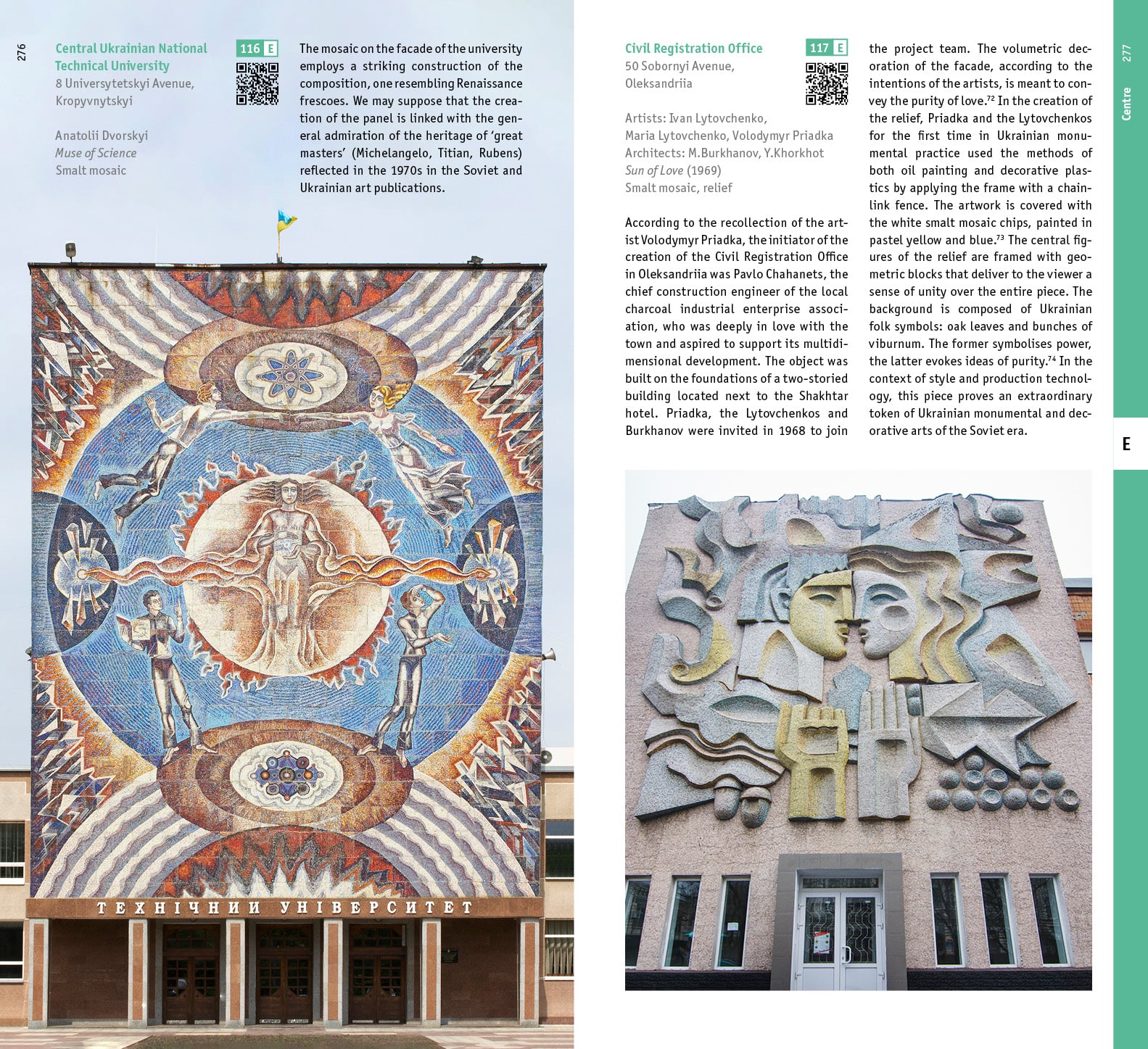

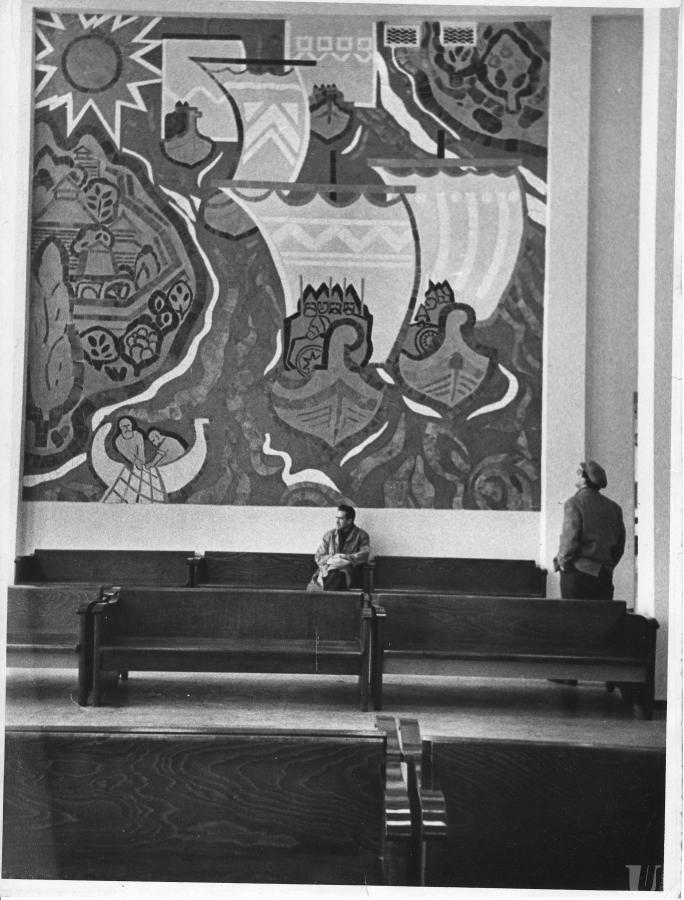

By Olena Lysenko

The majority of Ukrainian mosaics were created during the 1960-1980s. Thousands of residential buildings, houses of culture, kindergartens, cinemas, research institutes, industrial enterprises, and bus stops received brightly coloured ornamentations. The rise of monumental and decorative arts was linked with the rapid development of typical architectural projects. The main focus was on cost control, functionality, and “elimination of excesses in design and construction”. The beauty of the facade was no longer considered important, from now on buildings can stand end to end creating the microdistrict. Due to the appearance of such large empty spaces on the facades, they were decorated with mosaics, stained glass windows and reliefs, which included depictions of ordinary workers, scientific achievements, cosmonauts, motherhood, industrialization, and folk art.

The year 2013. Kyiv-based photographer Yevgen Nikiforov was commissioned to take photographs of Soviet mosaics for a book about 1960s Ukrainian art. Upon beginning the project, he was surprised to learn that relevant information was extremely scarce: little meaningful research had been done and no databases of the country’s mosaics existed. Even though numerous bright and colourful mosaics were scattered across the public spaces of many Ukrainian cities, they were often unseen and mostly remained as the relics of the totalitarian past. According to Olga Balashova and Lizaveta German, “Soviet monumental art failed to engage or enchant the public, both in the Soviet times and after Ukraine gained independence. It was treated as state-commissioned propaganda, not worthy of attention.”

This fact was so intriguing to Nikiforov that for the next few years he would travel to all regions of Ukraine frantically working to document the mosaics and make people notice them. His initial photography project was finalised in: Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaic published by Berlin’s DOM publishers together with Kyiv’s Osnovy Publishing in 2017. A big glossy art photo book, its release was a significant cultural event of the year in Ukraine.

In 2020, Nikiforov released Ukraine. Art for Architecture. Soviet Modernist Mosaics 1960 to 1990. Written in collaboration with art historian Polina Baitsym, Nikiforov’s second book is a practical guide to Ukraine mosaics for those who want to travel and see them with their own eyes. The book is supplemented with historical contexts, the process of creation, iconography, the biographies of the artists, and QR codes pointing to their locations. According to authors it incorporates all available knowledge on mosaics from the secondary sources, local press materials, the artists’ recollections, and archival documents. The book presents the selection of the most interesting, experimental art works from across Ukraine. Readers are given clear explanations about the specific style of different artists and how the themes of the mosaics differ from region to region.

But Nikiforov’s photographs are more than just photobooks; they are an advocacy campaign calling for the preservation of Ukraine’s mosaics. Interestingly, when people saw “old fashioned” mosaics on pages of beautifully polished artbooks, many saw them from new angles for the first time. After all, the theme of mosaics combines many levels of perception. First of all, they make a truly beautiful background for your Instagram photos. But if you dig deeper, you can also get to the issues of collective memory, including the question on how to treat artworks which were created during the Soviet past, is it art or propaganda, and the chance to learn more about prominent Ukrainian artists of the 1960s and their art, which as it turned out, was always out there as the public art for us to enjoy. Ultimately, thanks to Nikiforov, mosaics are considered cool once more in Ukraine.

Nikiforov’s public support is particularly important as mosaics are not legally defined as artworks and are thus not protected by the state. This means that owners of the buildings can demolish them without consequences. Unfortunately, such events do occur, often due to the ignorance of the owners of the buildings. The debate over the need to preserve mosaics arises in the context of the Law “On Condemnation of Totalitarian Regimes” (a.k.a. Decommunisation) that was passed by the Ukrainian Parliament in 2015. It should be noted that this legislation does not call for the destruction of works of art that were created during the Soviet era. It was mainly focused on dealing with the dismantling of monuments of Lenin and the renaming of streets which were named in honor of the leaders of the totalitarian regime. For those representatives of authorities who have some other understanding of this law, I advise them to study the legislation more closely.

Although the preservation of Ukraine’s mosaics depends on the enthusiasm of local activists and the sympathy of the relevant property owners and local authorities, there are also some positive changes in favour of their protection. On social media, Nikiforov has managed to create a large coalition of activists on his Instagram page Ukrainian Mosaics. Other activists in different regions of Ukraine, including the pages Chernihiv Monumentalism, Kakhovka Stone Embroideries, Ukrainian modernism have also begun to fight for the preservation of mosaics. In 2018, pop singer Onuka presented a photo project inside Kyiv metro, calling for the preservation of mosaics, located on metro stations. The following year, the Ukrainian Institute presented a video mapping that featured Ukrainian mosaics and contemporary electronic music in Vienna, and there’s also this awesome facemask by DIS/ORDER art group.

-

- Pop singer Onuka presented a photo project inside Kyiv metro, calling for the preservation of mosaics, located on metro stations © Alexander Dobrev

-

- The initiative Chernihiv Monumentalism transferred the mosaic, Ancient Chernihiv (1981) by Halyna Sevruk to the local museum

-

- Show your love for mosaics during the COVID-19 pandemic by wearing a facemask by DIS/ORDER art group

“The more people who will pay attention to mosaics, the higher the chances of protecting them,” explained Nikiforov. After the destruction of The Ocean mosaic in Lviv, the city council decided to introduce a register of mosaics, the same was stated by the Zhytomyr city authorities. In Kyiv, the mosaic, Wind by the legendary artist Alla Horska was given a protection status thanks to the work of local activists (before that, this mosaic was closed by a banner for decades). However, the registry is not enough and activists demand the proper legal protection for mosaics.

As a person who works in the non-profit sector, in particular on legislative reforms and advocacy in Ukraine, the struggle for mosaics personally reminds me of Ukraine in miniature, where there is a strong work of activists and volunteers who have high competence in the issue, they form strong horizontal ties in the community, and unfortunately weak state institutions who do not keep up with the current agenda. It was told by many art historians: because the phenomenon of mosaics is not yet fully studied, the destruction of mosaics will be terrible damage to the Ukrainian heritage and its value has to be defined by professional art historians and researchers.

Returning to mosaics, the book “Ukraine. Art for Architecture. Soviet Modernist Mosaics 1960 to 1990” reveals to us the fact that a large number of mosaics were created by some of the best artists of that time. They are familiar to us mostly not for their mosaics, but for belonging to the Sixtiers, the generation of intellectuals with powerful political position who demanded the preservation of national language, culture, freedom of expression during the temporary weakening of totalitarianism regime in the 1960s and Khrushchev Thaw. Sixtiers organized informal literary readings and art exhibitions, evenings in memory of repressed artists, staged plays, and composed petitions in defense of Ukrainian culture. Later, many Sixtiers became active participants in the dissident movement in Ukraine and were subjected to brutal repressions by the totalitarian state, were imprisoned, expelled from their creative unions, and purged, their works being destroyed. In 1970, mosaics artist Alla Horska was killed during unknown events, according to rumors by KGB for her attempts to investigate mass killings in Bykivnia and human rights activities. The book presents three of her unique mosaics, two of which are located in the war zones on the East of Ukraine.

Such artists lived a double life that included official and unofficial art. They created state-sponsored mosaics that were supposed to depict given themes. However, according to art historians, unexpectedly, there was a chance in monumental art for greater creative freedom. For example, as art critic Alice Lozhkina in her book “Permanent Revolution” points out, in the world where socialist realism was the only official art style, there were many examples of mosaics that featured abstract art that was then banned in the Soviet Union (during the Manege Affair in 1962, when Khryschev saw the abstract art he called it “filth, decadent and sexual deviation”, after the visit he arranged a campaign to tighten the grip of the Party over culture). Today, examples of abstract mosaics can be found at 17-27 Peremohy avenue and Olimpiiska Metro Station in Kyiv. Apart from that, artists secretly created “unofficial art” in which they experimented and expressed their creative freedom, organized unofficial art exhibitions, and formed tight communities of intellectuals, who frequently gathered in each others’ kitchens. This was in spite of the fact that the atmosphere in Soviet Ukraine was harsher than in Moscow.

In hard times during the totalitarian regime, mosaic artists were able to represent Ukrainian culture in their creative works and move away from direct propaganda narratives. The majority of the mosaics don’t have elements of apparent propaganda symbols, they are bright, colourful, and quite romantic decorations of the city. On the contrary, they often depict elements of traditional Ukrainian culture and folklore. According to the artist Victor Zaretsky, there were specific financial instructions that managed the categories of payment. “The artist was paid more for the image of the animals, compared to the floral ornaments, but less than for people. The highest payment was for the image of communist leaders”.

According to Nikiforov, many mosaics remain unattributed; we still don’t know the names of the artists who created them. “It is also an important part of my job to find the author of the work. I like the state of permanent search and I enjoy finding new and new objects, even if they are not very valuable”, said Nikiforov.

In my opinion, if you want to understand whether mosaics deserve preservation and protection, you need to study the biographies of artists who created them. Learning about the history of mosaics will also aid you in understanding the 20th century political and art history of Ukraine, particularly as their designers were some of the most prominent artists of the 1960s.

The book presents three mosaics of Valerii Lamah, the influential artist of monumentalism and the author of political posters. Among a close group of friends he was also known as a talented abstractionist, philosopher, and writer who produced The Book of Schemes, an illustrated manuscript containing his views on art and theoretic elaborations on the schemes of the universe. In the 1960s Lamah was one of the members of the community of intellectuals among them was the composer Valentyn Silvestrov, the architect of Tarilka building in Kyiv Florian Yuriev, the director of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Sergei Parajanov. Only in 1990, Lamah’s first exhibition of his experimental art was held.

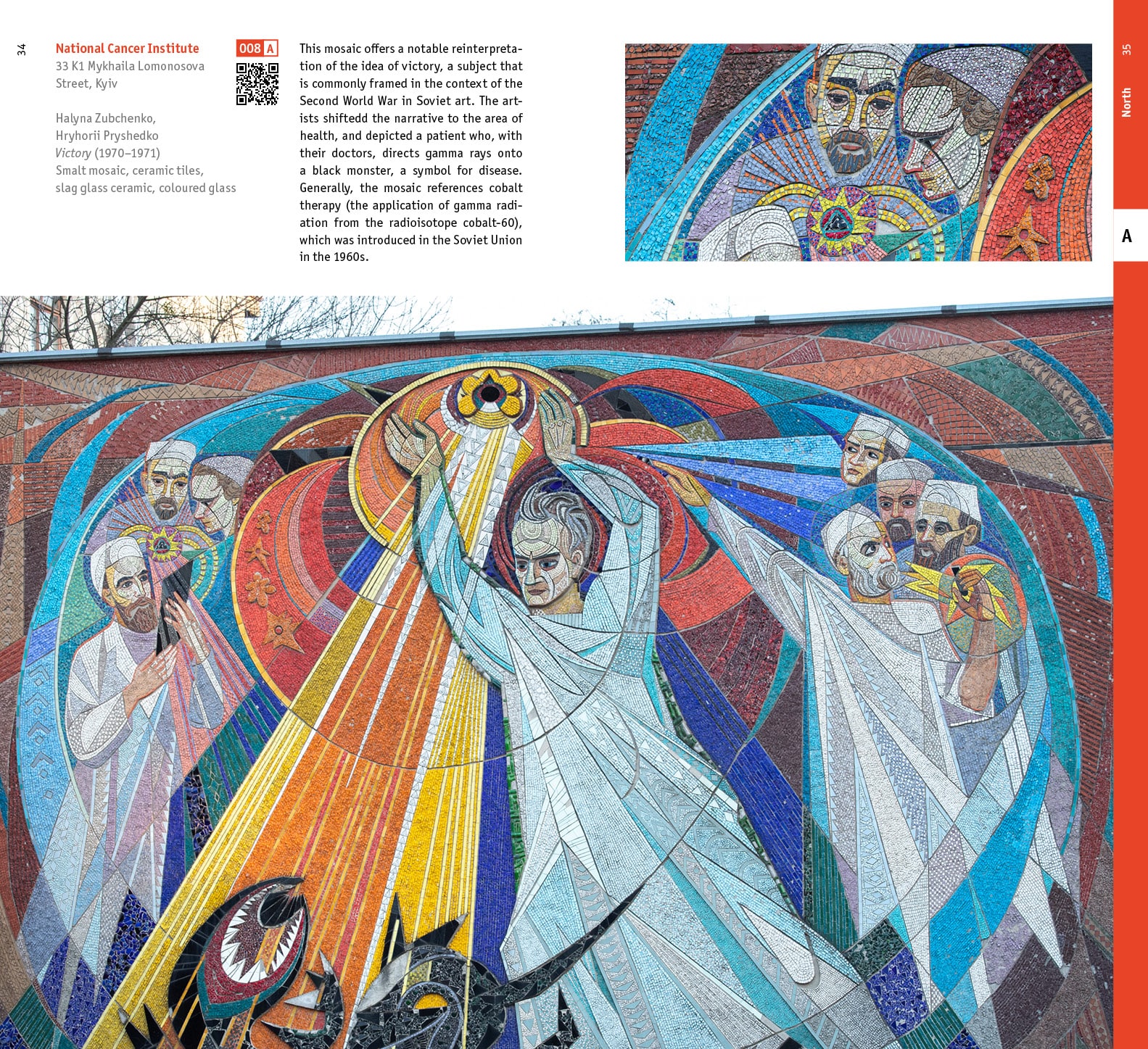

The couple Halyna Zubchenko and Hryhorii Pryshedko created one of the most expressive examples of monumental and decorative art inspired by science, their mosaics adorned the facades of research institutes and universities. The book presents five mosaics created by this duo, one of which at the Institute for Nuclear Research will be instantly recognisable to many, after it featured in the 2019 HBO miniseries Chernobyl.

Other mosaics that are featured in the book decorate the walls of the Nauka Sports Complex, National Cancer Institute in Kyiv, Aristocrat restaurant in Mariupol, and Experimental School no. 5 in Donetsk. Zubchenko was a talented painter, social activist, and member of the Club of Creative Youth, which was organizing unofficial art exhibitions, ethnographic festivals, and creative evenings. The members of the club were Alla Horska, Les Tanyuk, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstyuk, Sevruk Halyna, Ivan Svitlichny, and others. The members of the club experienced notorious censorship, when in 1964 authorities destroyed the stained-glass window Shevchenko. Mother, which was created by Alla Horska, Halyna Zubchenko, Luidmyla Semykina, Opanas Zalyvaha, and Galyna Sevruk in the hall of Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv.

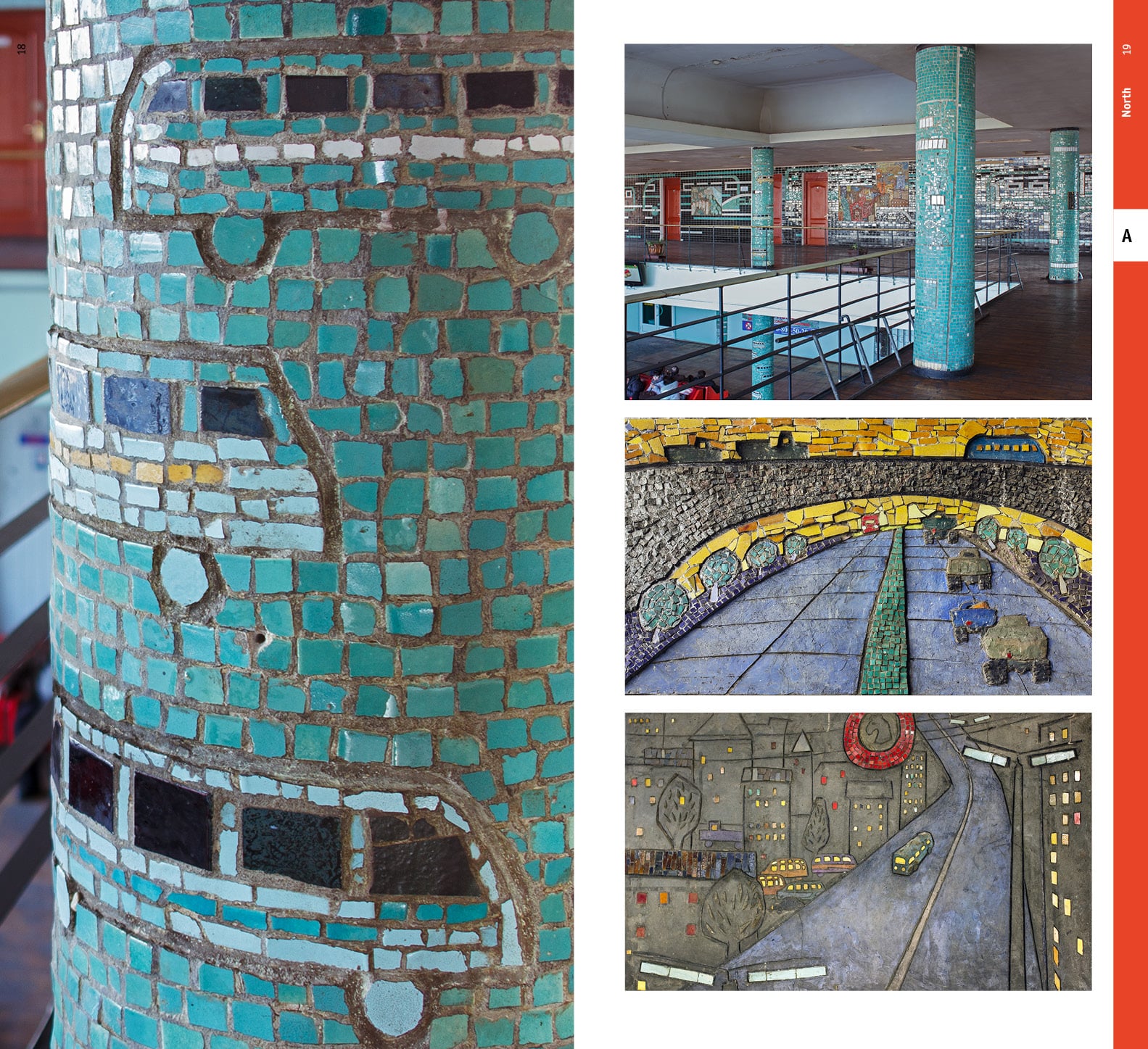

Another artistic duo who faced terrible censorship and whose works are also presented in the book were Volodymyr Melnychenko and Ada Rybachuk. Their most famous piece, Wall of Remembrance, the central to the composition of the Kyiv crematorium architectural complex, was known for being an epitome of an architectural invention. At the same time, the project is a rather infamous one. Soviet leadership blatantly ordered to suspend the monumental and decorative works, which meant the destruction of The Wall, as it wasn’t reflecting the Soviet values. This artistic duo also worked on sculptures, graphic designs, and children’s books illustrations. The book presents two mosaics created in Kyiv at the Central Bus Station and the Palace of Children and Youth.

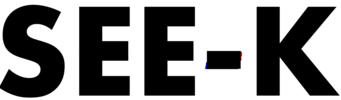

The book features four mosaics by Ivan Lytovchenko who devoted almost 10 years to decorate the city of Pripyat (now a ghost city after the Chernobyl Disaster) where he decorated three residential buildings, the cinema and the music school. As the authors of the book note, his designs feature an abundance of highly abstract artworks that tackle the subjects of light energy, occasionally supplemented with fragments of figurative images. For the artist the tragedy of Chernobyl was deeply personal, after the disaster, it was impossible to disassemble and transport the mosaics as they absorbed radiation.

The tradition of mosaics is not completely new in Ukrainian culture. One of the nation’s treasures and the symbol is Orans of Kyiv, 11th-century mosaic depiction of Virgin Mary in prayer, which was heavily influenced by Byzantine art after the adoption of Christianity in 998. Located in St. Sophia’s Cathedral which was built in the style of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia. It remained a political, cultural and spiritual centre for Ukraine for centuries, often serving as a place for major gatherings. The mosaics in the St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral, built between 1108 and 1113, miraculously survived the destruction of the cathedral by the Bolsheviks in 1934–1936 during the anti-religious campaign. Scientists managed to save some of the mosaics, now part of them are kept in St. Sophia’s Cathedral. The rest of the mosaics, reliefs, and frescoes were taken to Russian museums. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia refused to return these relics to Ukraine.

The authors of the book also mentioned how important the artist Mykhailo Boychuk was to the history of mosaics. Educated in Paris, Munich and Vienna, Boychuk returned to Ukraine in 1924 and became a professor of the Kyiv Art Institute. He was known for establishing his school which combined Byzantine influence with Ukrainian folk art in monumental and decorative objects. It became known as ‘Boychukisty’. However, in 1937, Boychukists together with Boychuk were executed in the forest in the village of Bykivnia near Kyiv on charges of espionage. As Polina Baitsym noted, the Boychuk case embodied the victory of Soviet art over ‘harmful influences of the West” and his name with the negative label ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’ was the specter which haunted the Ukrainian art world until Perestroika.

In contemporary Ukraine, Nikiforov’s research is part of an important phenomenon that contemporary artist and curator Nikita Kadan calls “a historiographic turn”. In recent years in Ukraine, there is a growing interest in studying the collective memory of the 20th century and the politics of memory among young artists and researchers. The tendency began after the Euromaidan Revolution in 2014 and the beginning of the Russian occupation of Crimea and the East of Ukraine. In her book “Permanent Revolution”, the art-critic Alisa Lozhkina noted that among, important projects which were the part of the “regional boom” such as the DE NE DE initiative led by Yevheniia Moliar, the researcher of Soviet monumental art. DE NE DE made expeditions to small local museums and art institutions near the war zone and documented their findings. The artist Vova Vorotniov made the performance @za_s_xid during which he walked for a month thousands of kilometers from West to East of Ukraine to transfer a piece of Chervonohrad coal to the collection of the Lysychansk Local History Museum. He documented his walk and posted photographs to social media. In 2014, while researching on Alla Gorska artworks IZONE art critics Olena Chervonyk and Liubava Illienko from IZONE art center created the website Soviet mosaics in Ukraine, the open database where people can submit photos of the mosaics. The modernist building of the provincial Kmytiv museum of Soviet Art, located in a small village, around 120 km from Kyiv, was transformed into a new exciting location for culture and art thanks to the participation of curator Nikita Kadan and young contemporary artists and already was called a Kmytiv phenomenon. Apart from that, there is a growing interest in the topics of Soviet modernism and brutalism in architecture among art critics, photographers, and filmmakers that seems like it will only grow more popular in the future.

Yevgen Nikiforov’s project combines the art of photography, the research, archiving, expeditions across the country. It began a discussion and made people notice the beauty in everyday objects. The publication of such books is not simply about the display of beautiful art but also a chance that these monumental artworks will be saved and finally will be seen as full-fledged historical achievements of Ukrainian architecture and be known on the international level.“I sincerely hope that innumerable explorers will dare to discover this country through these routes I have developed”, wrote Nikiforov.

“Ukraine. Art for Architecture. Soviet Modernist Mosaics 1960 to 1990” is available on the website of DOM Publishers.