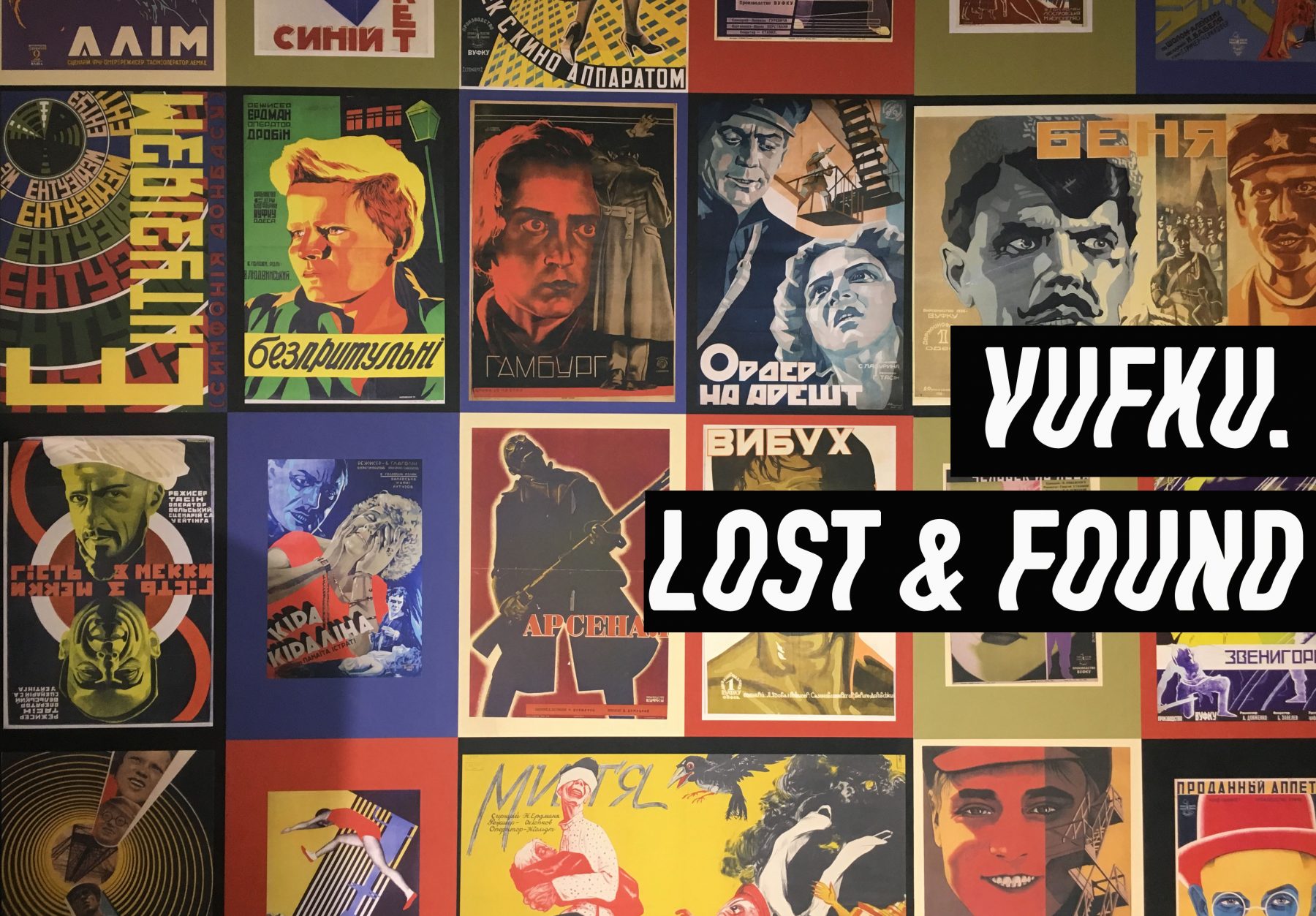

Museum of Cinema: Exhibition about ‘Ukrainian Hollywood’

Last September, the first museum of cinema opened in Ukraine with an exhibition called VUFKU. Lost & Found. Of course, we went in Dovzhenko Centre to have a look: first to the opening ceremony, a week later to a tour by the exhibition curators, later to see a cine-concert and then we read the catalogue of the project. Now it feels like we know about it too much and we are more than happy to share some insights and funny stories about «Ukrainian Hollywood» with you.

So what’s the whole fuss around VUFKU is about?

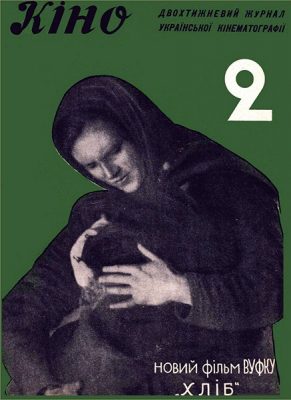

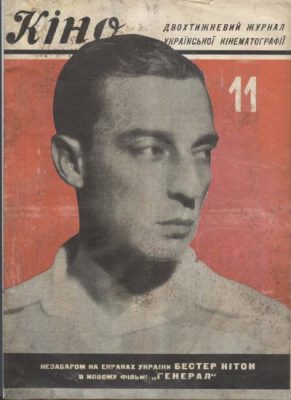

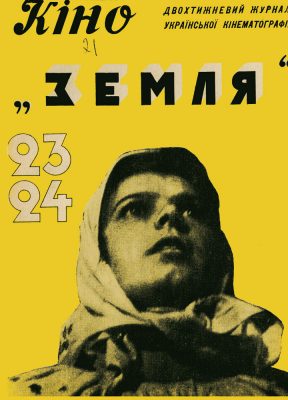

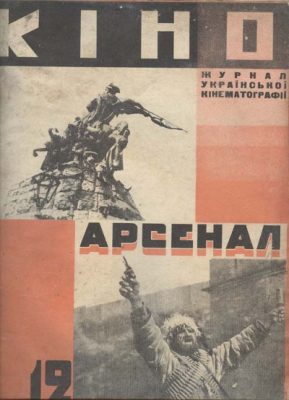

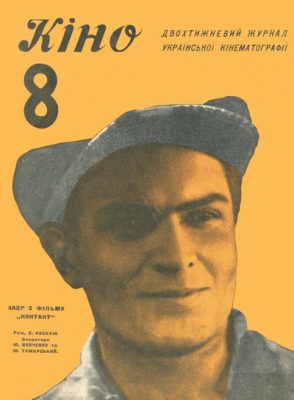

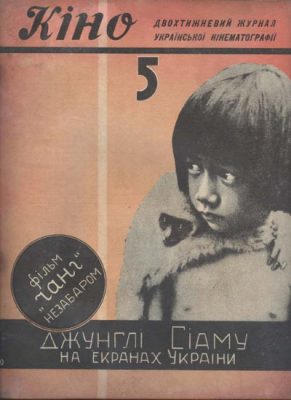

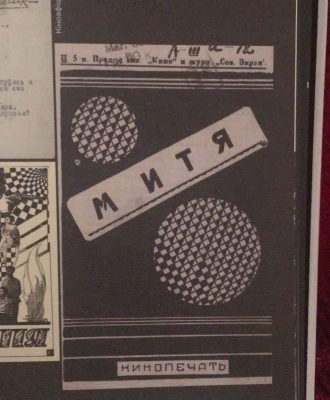

VUFKU or All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration has managed to release over 140 fiction films, several hundreds of non-fiction films and newsreels, dozens of animations in only 9 years of its existence. It was founded in 1922 in a very complex period of Ukrainian history in the context of multiple contrasting phenomena – social and nationalist revolution, Bolshevism, NEP, Ukrainization, the dictatorship of the proletariat, mass education, industrialization, terror etc. In the same year, it established Odesa and Yalta film studios, then in the space of 5 years, it constructed the largest film studio in Europe: Kyiv film studio (currently it is Oleksandr Dovzhenko film studio, located in Shuliavka district). In 1924, VUFKU created the first educational institution in Ukraine that offered filmmaking courses in Odesa. In 1925, it published the first issues of cinema magazine ‘KINO’ (see the images below). By 1927, Ukrainian films produced by VUFKU accounted for 37% of the film production in the entire Soviet Union. It is more than the number of full-length films produced in modern Ukraine.

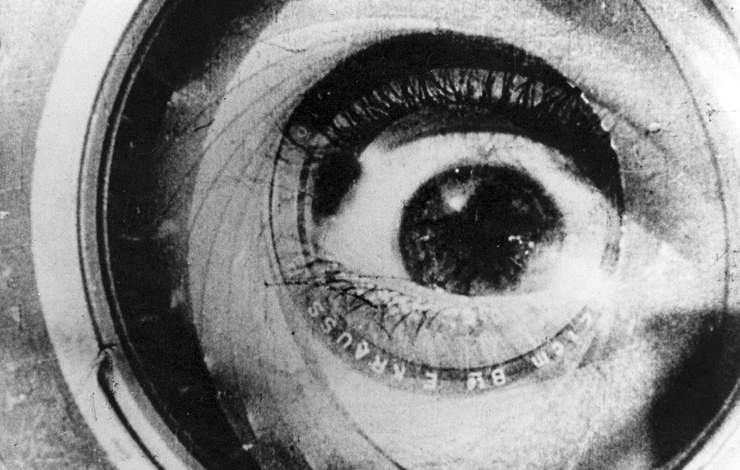

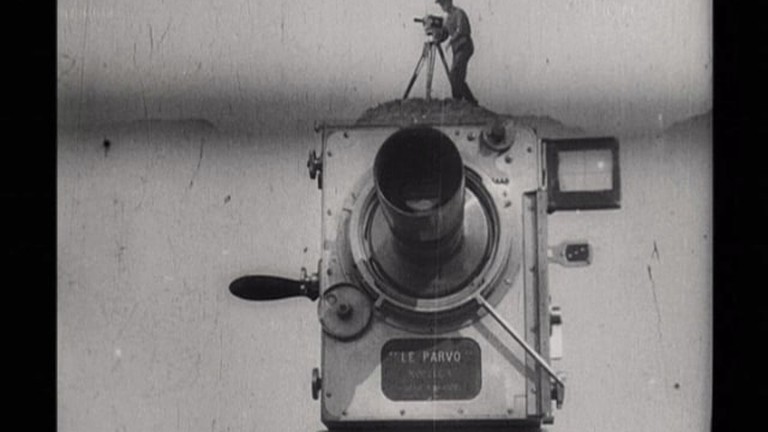

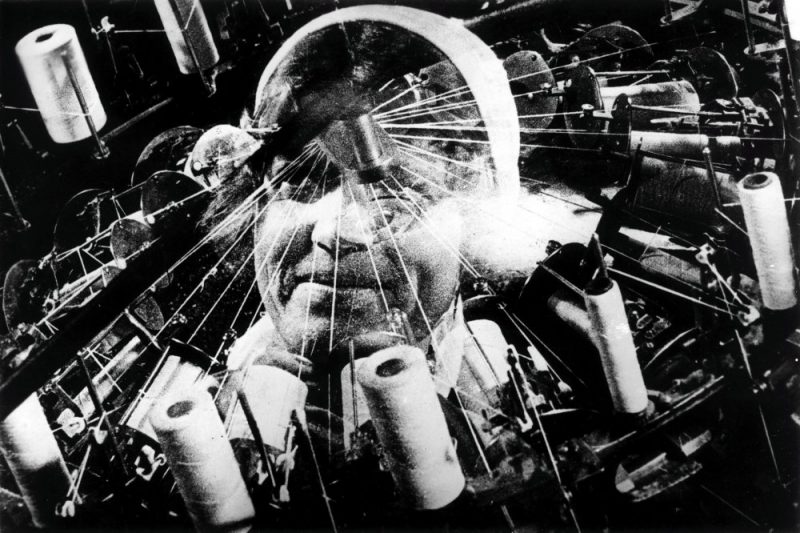

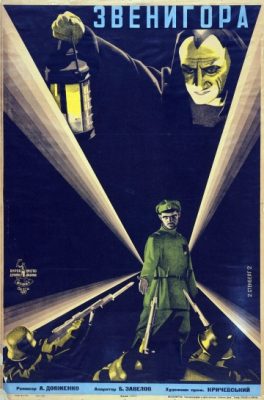

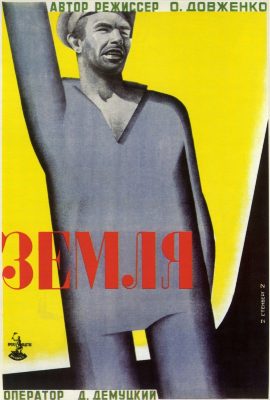

Throughout its existence, VUFKU had managed to gather around itself all the intellectual elites and the most outstanding artists of that times – the artistic association Berezil under the direction of the theatre director Les Kurbas, Ukrainian avant-garde and futurist authors Mykola Bazhan, Mykhail Semenko, Heo Shkurupii, Yurii Yanovskyi and Russian poets Vladimir Mayakovsky and Osip Mandelstam. Some of the most outstanding and well-known soviet films nowadays were produced by VUFKU: Zvenyhora and Earth by Oleksandr Dovzhenko, The Man with a Movie Camera and Enthusiasm (Symphony of Donbas) by Dziga Vertov. The later is, by the way, the first Ukrainian sound film.

Basically, VUFKU introduced mass fashion for cinema in Ukraine. But despite such great success and influence, in the 1930s, VUFKU became subordinate to Soiuzkino in Moscow and basically ended its activity.

5 reasons to visit VUFKU. Lost & Found

1. To see the Ukrainian version of The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station

If the history of world cinema began with a screening of the Lumiere brothers’ The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station’, Ukrainian cinematographers offer their interpretation of this narrative. A couple of VUFKU films, for instance, The Earth by Dovzhenko (see video below – starting from 27:20) terminates with the scene of a Fordson tractor arrival in the village. In the context of the collectivization (the policy aimed to integrate individual landholdings and labour into collectively controlled and state-controlled farms: Kolkhozy and Sovkhozy accordingly), the arrival of the tractor in the village was an ideological gesture to proclaim the irreversible progress of a new perfect soviet individual.

2. To get a glimpse on the stills from one of the slowest films ever made

One of the exhibition zones is dedicated to Ivan Kavarelidze – Ukrainian sculptor and filmmaker. In his debut work ‘Downpour’, he brought the statical and monumental characteristics of sculpture to the cinema language. The film is almost deprived of any motion and features a series of living paintings, performed by static actors with black velvet on the background.

Predictably, neither the audience nor critics weren’t ready to such a radical experiment in cinema history and Kavarelidze had to deal with fierce criticism. Unfortunately, the film hadn’t survived to our days and is considered lost, apart of a couple of stills.

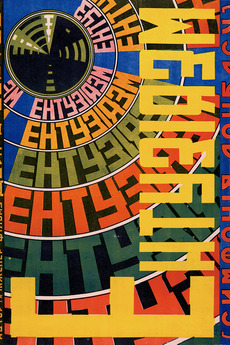

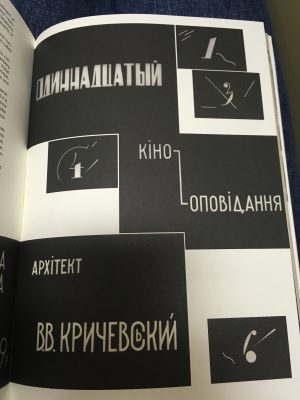

3. To check out some of the boldest artistic experiments with fonts and photomontage

Besides film, VUFKU produced supplementary materials – printed and illustrated posters, books in theory and practice of film production, magazines etc. Gradually, the artist had developed their visual style that is characterized by sharp shapes, dynamic compositions and contrasting colours, often combined in the technique of collage and photomontage.

We recommend paying attention to the artistically designed fonts!

4. To learn video editing from the best

VUFKU had also created its cinematography school that is recognizable by its usage of soft filters, constructivist diagonal and vertical shooting angles, static and contrasting images. Probably the most striking example is Mikhail Kaufman’s cinematography in the Man with a movie camera and Earth with cinematography by Danylo Demutskyi.

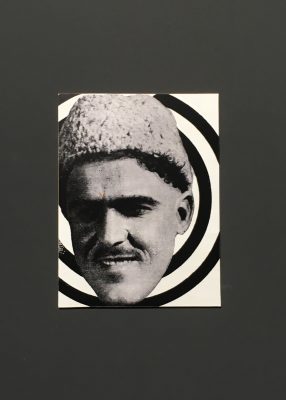

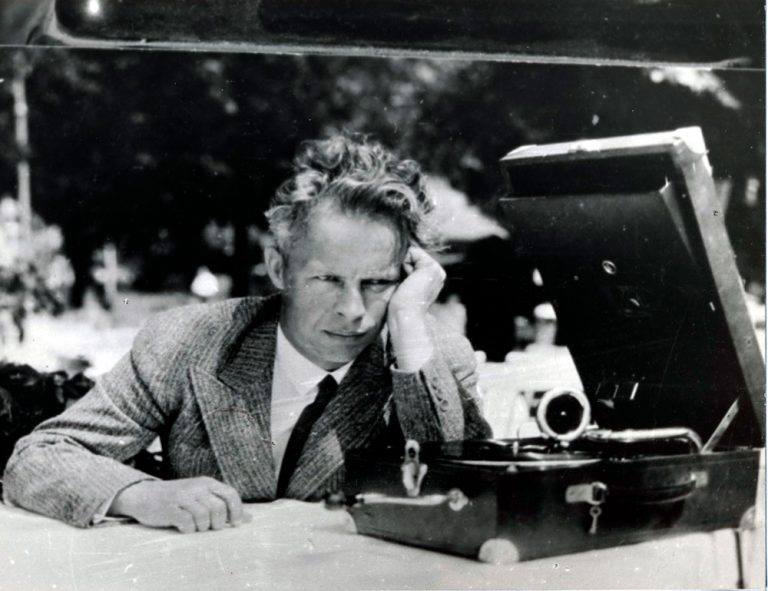

5. To see sad Oleksandr Dovzhenko

One of the most striking parts about VUFKU. Lost & Found is the curators’ work. The exhibition space is divided into parts that imitate different aspects of the cinema industry. In the same time, it follows the evolution of VUFKU – from its most daring projects to the saddest end. The final part is made of the red ‘corridor of terror’ – a powerful metaphor of ever more limited opportunities for Ukrainian artists towards the 30s.

The visitors can see there a gramophone that Stalin presented to Oleksandr Dovzhenko as a sign of his appreciation and indication on further direction of his work – to make only ‘right’ films about workers and benefits of the soviet regime.

Apart from the exhibition itself, the curators have also prepared a cycle of events, screenings, cinema-concerts and lectures dedicated to VUFKU. The programme is available here.

Source: VUFKU. Lost & Found catalogue