The Landscape Architect Who Takes Her Inspiration From The Paintings of Kazimir Malevich

March 21, 2020

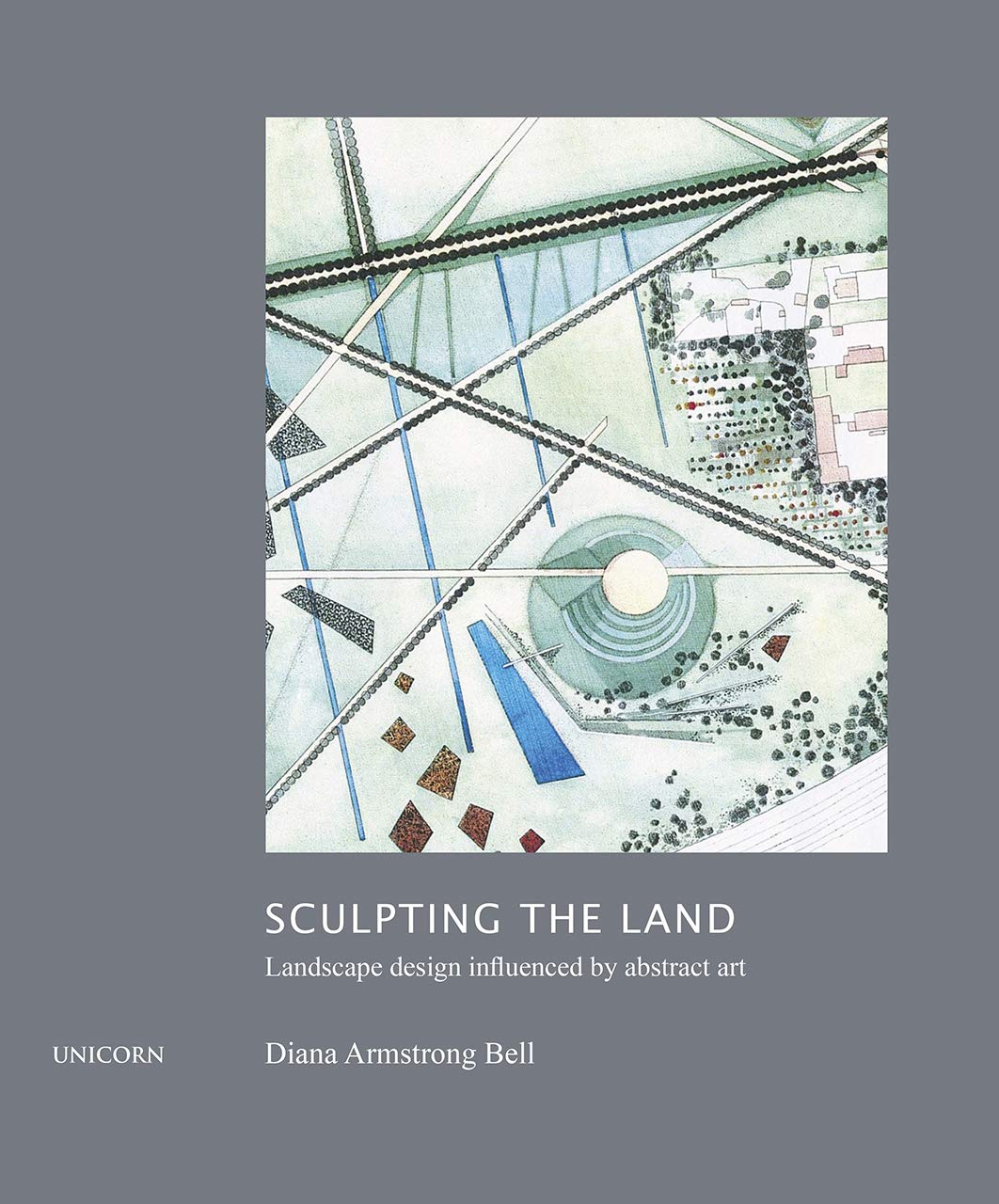

“Abstract art has always been an influence, a means of enriching my design thinking” explains British landscape architect, Diana Armstrong Bell, in her latest book “Sculpting the Land: Landcape Design Influenced by Abstract Art”. The founder of architectural practice, “Armstrong Bell Landscape Design”, she has won numerous awards for her designs of parks and the revitalisation of brownfield spaces across Britain, Italy, France. The book contains ink, watercolour and collage illustrations, photos of the completed projects, texts and shares the vision of the creation of landscape designs and how they came to life.

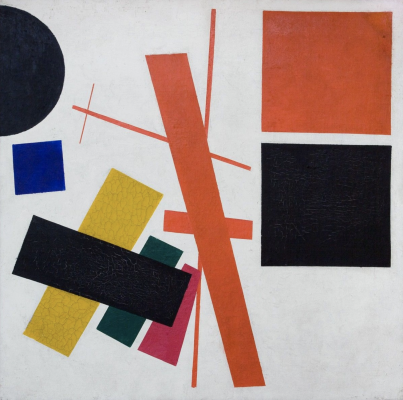

Diana cites the Suprematist paintings of Kyiv-born Kazimir Malevich as one of her main influences. “Using art as an inspiration in this way is all about looking. Time spent observing these works leads to an understanding of the visual language that Malevich developed, which can then be applied to landscape design. Particular paintings do not associate with any giver landscape, rather they influence a different approach to design as a whole.” In particular, Diana suggests that one should look for clues in Malevich paintings to find atypical ways to organise space and cast aside the traditional practices such as classicism and historicism.

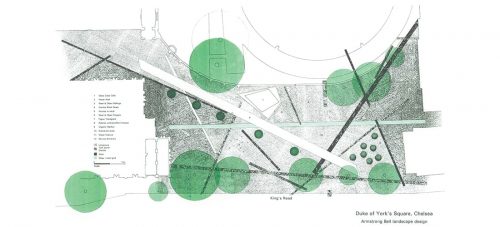

From a top-down view, Armstrong Bell’s landscape project for Electra Park in London looks indeed like an abstract painting. The viewer’s attention is driven to the silver granite square and a long bench, which create an abstract geometry. This park used to be a power plant, which was later cleared, leaving the site contaminated. The project represents more than just a group of utilitarian objects which “just have to be there”, but rather an intelligent organization of green space that aims to make people pause and reflect.

In his texts’ Malevich describes the emergence of suprematist composition as the mythological birth of the cosmos out of chaos. He aimed to create the harmonious, elegant system where geometrical shapes such as circles, squares, etc. moved and alternated on a canvas (and beyond the borders of the canvas) according to the certain laws of the rhythms, the “music of the spheres”. According to art critic Irina Vakar, Malevich created the space that had to be simultaneously free and ordered, containing a complex yet clear organization of spatial relationships and forms, of movement and stillness. The specialist in avant-garde art Christina Lodder, has noted that Malevich avoided right angles and placed the forms in irregular relationships to each other and to the frame of the canvas.

Diana believes that these paintings can be read as a notion for the design of cities, landscapes and buildings. It’s quite logical to perceive Malevich’s paintings as an inspiration for the architecture since he was also creating three-dimensional architectural models himself, which he called “architectons”. In 1918, he wrote that the abstract forms of his suprematism paintings and the ideas underlying their production could play an important – although essentially supportive, rather than initiatory – role in articulating the environment in the nearest future. The connection between the top-down view and his suprematist works can be found in “Airplane Flying”, a 1915 painting, whose name directly refers to aviation.

Apart from the visual component, Diana believes it is important for the architect to gather fragments of a site’s history and use it as a source of inspiration for the design. “The land is never blank, it is up to us as designers to find its story and connect a landscape back into its context”, notes Diana.

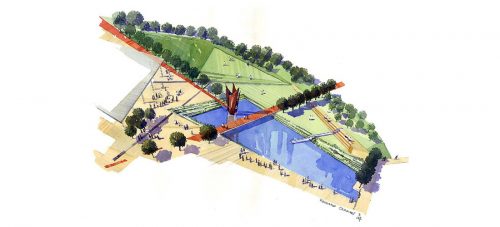

For instance, when she was working on the project for Parco Franco Verga in Milan, Italy, she learnt that water played a crucial role in its history. The old city map brought to light the fact that Milan was encircled by canals, but in the 1920s and 30s a programme of covering the canals and converting the spaces to roads changed the whole feeling of the city. She emphasizes that the crucial part of the design process is to understand what memories are contained within the site and its residents. “It means spending time in a landscape, observing, listening and gathering clues to inform a new story. This is especially the case for brownfield sites which may first appear devoid of clues, a blank canvas”. For the design of the park, which was previously contaminated by the oil industry, Armstrong Bell used earth modelling and water to create a new story for the landscape; as a result, this project became one of the most visually striking and interesting projects of hers. Roads and canals filled with water were built into lines; the water area near the playground is now used by residents as their own beach and a place for a picnic.

Armstrong Bell sees trees as the green architecture, green building blocks in the urban environment that can establish spatial boundaries, create the walls and ceilings of outdoor rooms and give urban space a sense of human scale. “In parks and open spaces, trees can be used to define space, create vision corridors and give structure. Groups of trees can bring flow and informality; they can weave their way through structural grouping of trees or built structures”.

Her landscape design of the Sainsbury Wing Piazza in London represents this particular idea. The trees for the project were planted in grids that aimed to bond together the space that links Trafalgar Square with Leicester Square. Six trees planted in a grid transformed the space, which suddenly became an outdoor room, crowns formed a “ceiling”. “What had seemed like an odd piece of “land left over”, assumed an identity. It became a space where you might linger on your walk though”. Diana cites different forms of nature as her inspiration such as earth lines, lines and patterns in the landscape and emphasizes that they have imprints of human history in them.

The public spaces, especially those that include nature are important elements in the city that aim to bring opportunities for its residents to come together, build a community, make neighborhoods a better place. When public landscapes are created with people in mind and have art at their core they have all chances to last for many years and create a new page in the history of the city. In the words of Kazimir Malevich, we should prioritize the eternal over the fleeting, as he wrote “to perpetuate on the wall something which would obsolete tomorrow is a mistake”.

During our communication Diana noted a great connection: “Kazimir Malevich was born in Kyiv. It’s a lovely story that he is still influencing designers 100 years later”.

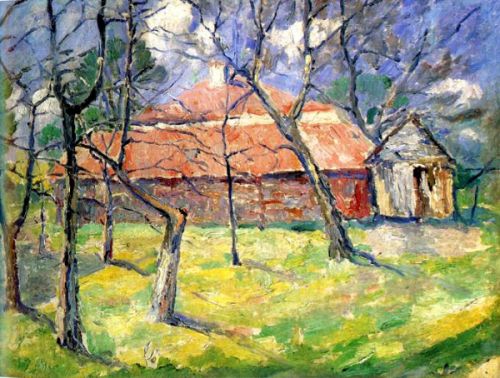

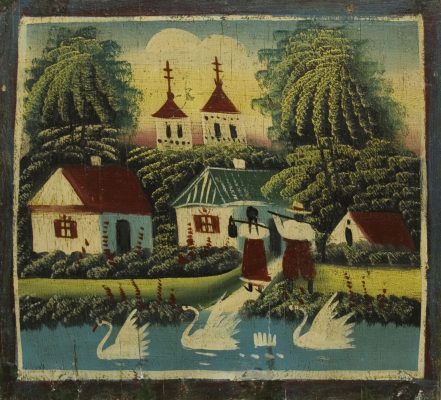

Malevich and his art had indeed a strong connection with the city of Kyiv. Born in 1879 in Kyiv, he spent his childhood in villages across Ukraine, where his father worked as an engineer at sugar factories. During these years he visited Kyiv many times. It was a place where his mother bought him his first paints and where he trained as an artist. Kyiv became a source of intense emotions and the major influence for him, as he noted in his memoirs: “From year to year I grew more firm in my striving [to become a painter] and I was more strongly feeling Kyiv’s sway over me. The city got amazingly deeply lodged in my awareness. The houses built of red brick, the hilly environs, the Dnipro, the vast horizon, the steamers. All the city’s life exerted more and more influence on me. Village women crossed the Dnipro in their rowboats, bringing the butter, milk, cream; they filled the wharf and the streets of Kyiv, generating a special atmosphere and color”.

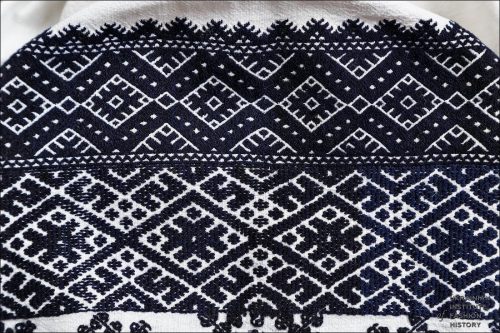

According to art historians, Dmytro Horbachov and Jean-Claude Marcadé, the time Malevich spend in Ukrainian villages as a child made a huge influence in his artworks and the geometrical shapes in his suprematist paintings evolved from Ukrainian traditional art, its colors and shapes. The end of the 19th century, the time that Malevich had witnessed as a child, is known for the heyday of Ukrainian traditional culture (folk paintings, wooden toys, pottery, embroideries, church icons). In the village where he was living the wall paintings were decorated with archaic forms like stripes and dots. In his memoirs he talks about this times: “Village… was engaged in art (I didn’t know that word at the time, thought)”.

During his later years when he was living in Kursk, Moscow, Vitebsk, Leningrad, he never broke off his bond with the Ukrainian colleagues and was a regular contributor to local art magazines Nova Generatsiia and Avanhard-al’manakh. Malevich returned to Kyiv in 1928 to take up a professorship at the Kyiv Art Institute (today – The National Academy of Visual Arts and Architecture). He had his own classroom where he was “healing students from realism and the fear of colors”. During that time he had a friendly relationship with Kyiv-based artists Oleksandr Bohomazov, Victor Palmov and “spectralists” which were the members of Association of Contemporary Artists of Ukraine.

“Sculpting the Land: Landcape Design Influenced by Abstract Art” is available at Amazon and on the website of the Unicorn Publishing Group.